Earlier this year, a few of us visited a friend who recently moved to New Mexico. It was a whimsical trip. We mixed in some camping in Cloudcroft, wandering dunes in White Sands National Park, and lounging in the weirdly hip town of Albuquerque. Aside from eating a lot of hatch green chilies, we bounced around art galleries in downtown, taking in paintings, photography, and prints inspired by the southwestern desert sun. Inspired by the trip and feeling the urge to activate a side of my brain I had not touched for a long time, I joined a local art studio.

As a kid, my mom enrolled me in drawing classes. I was one of those kids that hated being forced to do anything (turns out, I’m one of those adults as well). As a result, I didn’t enjoy the class. All I remember is this: sketching the shadows of an apple under an artificial lamp was boring as hell.

However, I was decent at drawing. The only reason I knew was because of how bad my brother’s drawings were. My family and I sometimes pull up his drawings to get a kick out of it:

Good thing he’s a Data Engineer instead.

This is a sketch I did in middle school:

It’s my favorite character from the anime series Naruto. I remember it didn’t take me very long and I was very proud of it (proven by the fact that I still have this two decades later). Looking at it today, I have no idea how I managed to do this. So, into the art studio I went.

6 months later, I’m writing this post to document my learnings and experience learning from foundational concepts.

Since I wasn’t forced into class, I skipped into my first drawing class. The class is a mix of very young high schoolers prepping their college application and mom’s & grandma’s working on paintings of their dogs, children, and grandchildren. Then there’s me. After a few sessions of “what the hell am I doing here” type of thoughts, I accepted my situation and decided to enjoy mixing with people I wouldn’t normally cross paths with.

The teacher, José, is fantastic. He doesn’t beat around the bush and is constantly pushing students. He’s the exact type of teacher you want if you want to get better at anything: someone who won’t let you rest on your laurels, will call you out when you’re slacking or underperforming, and push you just beyond your ability without discouraging you.

The first thing I learned is that drawing is extremely technical. This is probably obvious to most of you, but for some reason I thought artists just draw whatever they want in whichever style they want. José asked me a simple question in my first class: are you just trying to paint something or do you actually want to learn how to draw from the ground up. He was telling me that learning to draw from basics will build a foundation that makes everything else in the future easier—whether painting, pastels, watercolor, and so on. So, I opted to build a foundation.

Bargue: Sketching with Graphite

To start, José had me working out of a classical textbook: Bargue. I started out figuring out how to sketch simple detail, from a nose, to an eye, to the simple outline of a face. With sketching, the rules are to: stay loose, draw light lines that go out to infinity, spend more time observing your subject than your own drawing (true at all stages of drawing), work with the large bits of information first before moving onto the smaller detail, measure proportions of the large pieces of information, but remember that it’s a sketch, you’re not trying to perfect it on the first go.

Dark vs. Light with Graphite

From there, we went into discerning dark and light. Here, I learned that contrast is what gives a drawing life. Blocking is the act of “coloring” or “shading” a particular area to denote a dark, typically done with consistent strokes that don’t seesaw like a seismograph. They should be consistent across size, space, and direction. Once again, look at the large details. What are the darkest areas on the subject? Start with the darks first, be consistent with your values across a piece. Find each value across the entire piece before moving onto the next value. The piece should look “completed” even if they are at different stages, for example 10 minutes vs 10 hours. Direction of blocking should follow the lengthwise of your object, but consideration should also be given to texture (for example, rounding or flatness). The Asario Head is a good reference for drawing faces. You need a light next to a dark to see the dark. The reverse is also true. Be suspicious of any places that have a line and lights on each side. Dark next to light, light next to dark, contrast is what creates the drawing.

Values with Graphite, Charcoal

Dark and light naturally gives way to values. Because this isn’t black vs. white, dark and light implies that there is a degree to how dark or how light. Before moving onto colors, we spent a lot of time better understanding blocking in the context of values. If you block consistently in a single direction you can only add the density or increase the value of the shading so much. If you introduce crosshatching, you can add more texture and have more values that are more or less dark and light. You have a larger range of textures to play with. When cross-hatching, make sure not do do 90 degree crosshatching. Consistency in direction will take the life out of a drawing, most things in nature don’t only go in a single direction, for example, someone’s hair!

During this period, a lot of my drawings would look nothing like my subject. However, if I ignored that and pressed on, eventually it would look very much like the subject. My drawing looked completely messed up, kind of like a blob, less like a blob, and eventually, more like what I intended to draw. It’s a fun and infuriating process, kind of like writing a blog post about something you know nothing about.

Pastel

After a solid 4 months of a couple sessions every week in black and white, we finally moved on to some color! I was itching to get to this stage because it’s what I imagined when I stepped into the studio. But we were building the foundation!

We started with pastels, which conveniently have a similar feel to charcoal which we spent some time on at the end of the black and white era. At first, it was very weird sketching with pastel. Which color do you even use? Once again, you go with the dark and light. What are your darkest values on the drawing? Pick that color. For the hummingbird I started with was a bluish green. José purposely started me on a pastel set that did not have any range of whites or blacks. This forced me to understand the color wheel, which is something most 3rd graders know more about than I do. RGB!

Some basics to the color wheel include: Colors on the color wheel next to each other mix well, if they are across they go well together but they do not mix well, they are how they get your grays and browns (mostly brown), complements mean that they do great next to each other (think Red & Green for Christmas), but the moment you mix them, they get muddied out. In most cases, a muddy effect is done via layering complementary colors. Black is not a color, there’s always some color to black. For example, I used a lot of blue and purple to get the dark parts of Messi.

Pastel is very forgiving, so stay loose with it, test out colors, and make adjustments as you progress. In most cases, the first color you pick won't be right. Don’t be afraid of making mistakes. For transition areas, the dark of a light is usually the light of the next dark and vice versa, depending on which direction you are moving. Important to consider warm and cool colors as well. Colors that jump out are vibrant, high saturation colors, not necessarily white. Colors develop like a sketch: at first, your colors look completely off, but as you build layers, you slowly inch towards the result you’re targeting. Stay patient with it, experiment, make mistakes, and adjust.

Tricks of the eyes: Our brain will blend colors to create a dark, hence, adding brown or blue to dark spots in hair makes it appear darker than just blue or black. The brain will draw lines, we just have to draw suggested lines to help the brain out. For example, drawing an iris doesn’t mean outlining the entire iris, just draw a portion of it and our eyes will connect them, same thing for space between teeth - don't draw the full line between teeth, otherwise it will appear like your subject has gaps between their teeth. Just a portion of the lines on the top and bottom of the teeth and the brain does the rest. Consider the texture of what you are drawing to determine which stroke you make.

A Messi evolution below:

Floor plan of 196 square foot studio drawn by child.

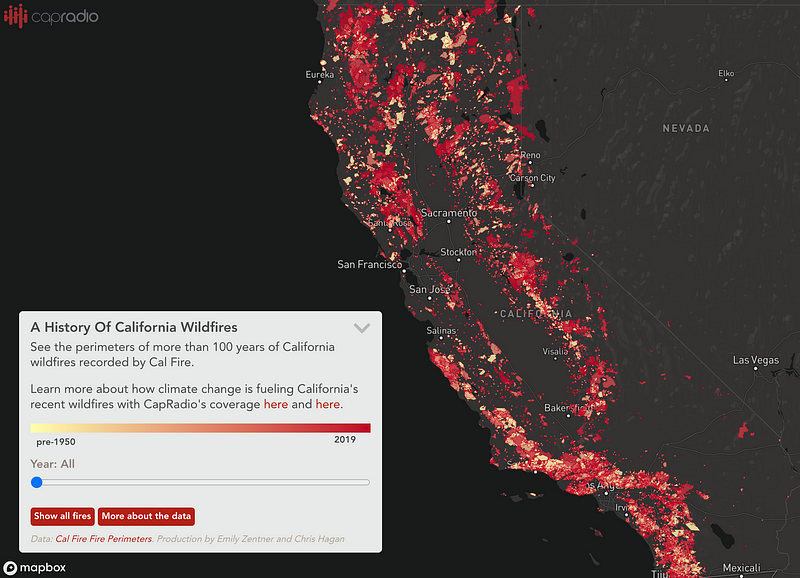

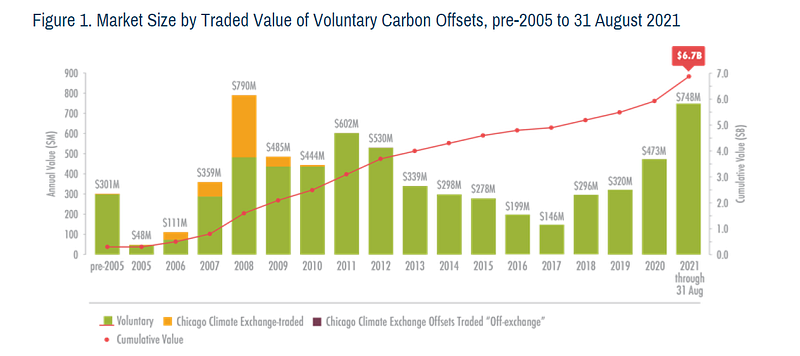

Floor plan of 196 square foot studio drawn by child. Growing voluntary carbon market from 2005 to 2021. Source.

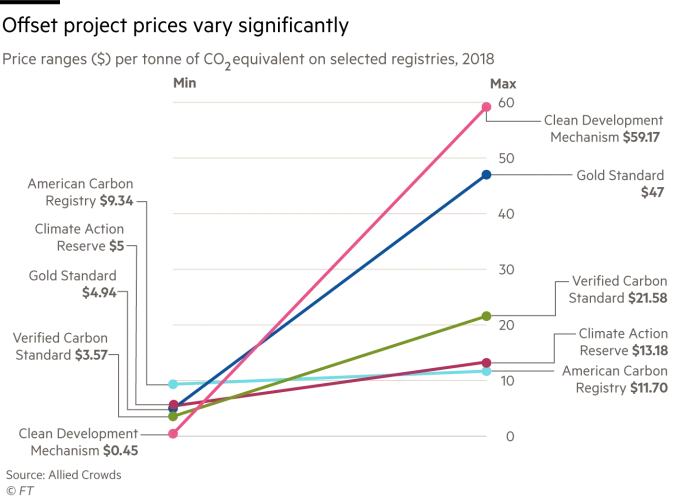

Growing voluntary carbon market from 2005 to 2021. Source. Variance of carbon credit prices, both between and within registries.

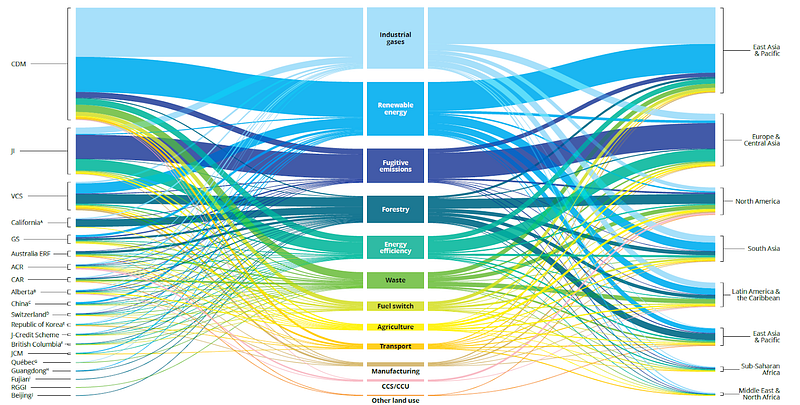

Variance of carbon credit prices, both between and within registries.  The range of carbon credit project categories by registry and region through 2019.

The range of carbon credit project categories by registry and region through 2019.